How do Montessori Guides Address Avoidance?

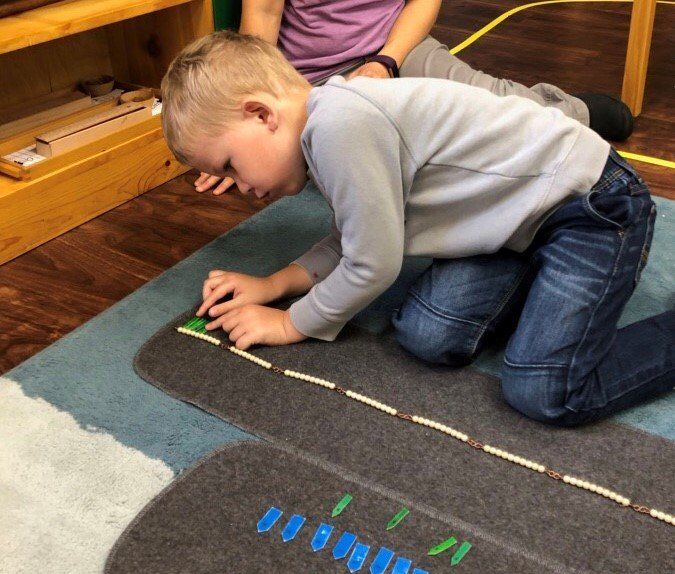

An example of an elementary child’s work record

One of the questions asked about Montessori education is: How do teachers deal with children avoiding work they don’t want to do? This is an important question, and it becomes increasingly so as children get older. Montessori philosophy centers on child guided choice. It can be hard to envision that value working in conjunction with accountability. The Montessori approach enables children to develop strong work habits and encourages them to be driven by internal motivation rather than to imposed external factors.

Give Them Choice

Having choice is a powerful tool in combating avoidance. Knowing that others trust in us to do the right thing is often all it takes to do the right thing. No one likes to feel micromanaged. We allow children to choose the order of their work; some like to start the day off reading, while others prefer math. We also let children have autonomy in other ways. They decide when they need to use the bathroom, have a snack, and move their bodies. There are, of course, procedures to follow to keep everyone accountable, but we believe children shouldn’t have to ask permission to address their basic needs, nor should they have to do so on a schedule that is convenient for adults.

The big picture: children that feel respected and trusted are much more likely to work hard and meet expectations.

Quietly Observe

If there is one statement that can help us reframe our perspectives with empathy, it’s this: Each child is the way they are for a reason. There is a reason a child may be avoiding something. As adults, it’s our task to discover what that reason is, and find gentle ways to address it. Guides use observation as a way to learn and make more informed decisions. Some questions we may ask ourselves as we observe a child who is struggling:

● Is the work too challenging?

● Is the work too easy?

● Is the child experiencing emotional upheaval?

● Are the child’s basic needs being met?

● Is the physical classroom environment supportive of the child’s work?

When Montessori teachers are trained, they learn to first look to the environment, then examine themselves and their own actions. Only after considering the first two possibilities do they look to the child themselves as a potential source of the issue.

Appeal to Their Interests

Sometimes what children need is a ‘hook’. Although Montessori materials in the classroom are meant to be used in a very specific way, and deviation distracts from authenticity and effectiveness, there is some room for flexibility. This can be very helpful in modifying work so that it will best meet an individual child’s needs. A guide may consider a child’s favorite color when setting out pouring or scooping materials, favorite animals when presenting zoology lessons, or other interests when gathering reading materials. The key is to consider what a child is avoiding, then find a way to make it more enticing.

Hold Them Accountable

While Montessori doesn’t use punitive measures, that doesn’t mean we don’t hold children accountable. If we expect children to do certain things, it’s our job to make sure they follow through. The following are critical in making this happen:

● Clearly explain the expectations.

● Provide an environment and time that allows for expectations to be met.

● Observe children to ensure they meet expectations.

● Guide when necessary. This may include redirection, suggestions, or working together to create a plan.

As children get older and academics become more of a focus, getting work done becomes much more important. Beginning in the elementary classroom, children begin to usework journals. These can take on a variety of forms butserve as a visual schedule of the child’s work, created in collaboration between the guide and the child. Children can typically choose the order in which tasks are completed, but adults check in to make sure there is follow through. In the event the child is not meeting the expectations, a guide will meet with the child to discuss new strategies. They may help the child develop time management strategies, give suggestions as to seating, or provide tips for effective work habits. The child leaves the meeting with concrete strategies to try, and the adult and child reconnect at some point to evaluate progress.

It helps to remember that learning to work is part of the child’s work. Rather than forcing children to do what we want when we want them to, we take a more long-term approach. Our goal is not just to share information, but to help children become joyful learners. We want them to feel confident in their abilities and ready to take on challenges. We all want to avoid certain tasks from time to time. Our job is to guide children in managing their time well and in accomplishing whatever it is they need to get done.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this work can be carried over into the home as well. The more families learn about Montessori, the more the concepts become part of parenting and the life of the child. We hope you will reach out to us if you have any questions.

PROGRAMS

St. Croix Montessori School

Nido Montessori School